Oil prices are at a record high, causing inflation to rise across the world. The petro‑monarchies are rolling in cash. Popular press is shrill with the 1970s redux headlines: stagflation, petrodollar recycling, debt crises. Experts and talking heads are telling us how by the next decade we’ll have run out of oil, or Saudis will go the Iranian way, or we’ll be driving hydrogen cars.

But it wasn’t that long ago that talking heads and experts were singing a completely different tune. No less an authority than the Economist said in March 1999 that the next oil shock would be a dramatic fall in oil prices, with the consequences being ‘not as good as you might hope’. Subscription is required to access the article. The highlights include the following sentences.

- Oil in the Gulf is cheap to extract—barely $2 a barrel, a quarter of the cost in the North Sea.

- $10 might actually be too optimistic. We may be heading for $5. Thanks to new technology and productivity gains, you might expect the price of oil, like that of most other commodities, to fall slowly over the years.

- Nor is there much chance of prices rebounding. If they started to, Venezuela, which breaks even at $7 a barrel, would expand production; at $10, the Gulf of Mexico would join in; at $11, the North Sea, and so on.

- There is another threat on the demand side: worries over global warming.

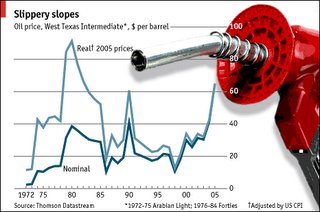

Just in case you are wondering whether oil prices indeed fell after 1999, they doubled within a couple of years, well before the War. The chart above appeared on the 12 August 2005 issue of the Economist. Since then, crude oil prices hit US$70 a barrel in the aftermath of the hurricane Katrina, and are now selling for around US$60 per barrel, about where the market suggests the price will be for the foreseeable future.